Make It Personal - The Best Photos Start From Within - Jens Krauer’s In Plain Sight Is Proof

Welcome to this edition of [book spotlight]. Today, we uncover the layers of 'In Plain Sight: Candid Urban Encounters,' by Jens Krauer (published by Kehrer Verlag). We'd love to read your comments below about these insights and ideas behind the artist's work.

You don’t need expensive gear to make meaningful images.

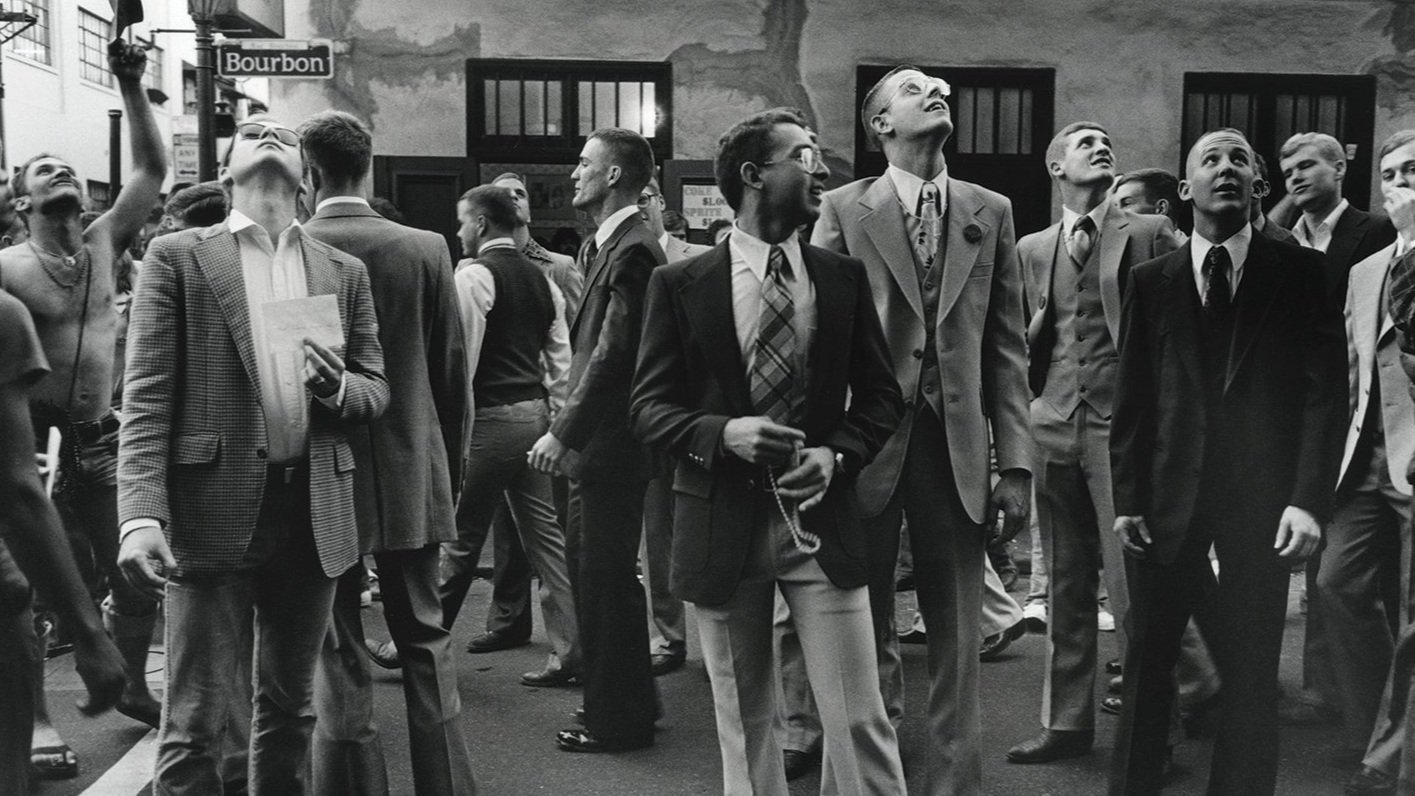

Jens Krauer shows that with one camera, one lens, and a strong personal vision, it’s possible to build a serious body of work. He spent ten years walking through cities like New York, Paris, and Istanbul, capturing moments that most people pass by.

Jens Krauer didn’t follow a traditional path into photography.

He learned by walking, observing, and trusting his own perspective. Instead of planning every shot, he spends hours on the street, waiting for something real to appear in front of the lens. This method is not fast, but it builds a deeper connection with the place and the people. His new book In Plain Sight focuses on real life in public space, not staged scenes or dramatic events.

In Plain Sight: Candid Urban Encounters

For ten years, Swiss street photographer Jens Krauer walked through major cities such as New York, Paris, Amsterdam, and Istanbul with a camera and a single lens. In Plain Sight is the result of this long-term project. The book brings together his strongest black-and-white photographs, capturing unscripted moments in public space with honesty and emotional depth. There are no staged scenes or digital effects. Each image reflects Krauer’s commitment to observation, patience, and presence. The book features 73 duotone photographs and includes texts by Chris Gampat, Stella Kramer, and Jamel Shabazz. Published by Kehrer Verlag. (Kehrer Verlag, Amazon)

Overview of the project: What motivated you to dedicate a decade to capturing candid moments in the world’s metropolises, and how does In Plain Sight reflect your vision as a street photographer?

Through my personal life story, I have developed a deep connection to the streets and the fringes of society. I haven’t just observed different social classes—I have lived within them for extended periods. That’s why I feel most at home in the raw, dynamic tension of the streets, where all layers of society intersect.

In my youth, I engaged in what I call the unsolicited beautification of urban spaces. Back then, it was spray cans in my backpack; today, it’s a camera, a passport, and a notebook. But the mindset remains the same: the street is my creative space.

Photography found me ten years ago—I didn’t seek it out. When it did, I carried my street-born attitude into it, quickly finding my place in an environment I already knew intimately. Photography became the perfect medium for me to explore and document the world.

The concept for this book was developed in collaboration with Kehrer Verlag, based on a selection of the best images I captured over the past decade. Once my images are finished, I embrace the process of letting go—shaping the final form alongside other creative and talented individuals. When it comes to presenting my photography, I trust external perspectives and expertise. This collaboration is incredibly enriching, offering fresh insights that elevate the final product.

I believe street photography should speak for itself. That’s why the book contains minimal text, aside from contributions by longtime collaborators and artists I admire, allowing the photographs to take center stage. This book is a collection of the finest images from my street photography over the past ten years—the result of thousands of kilometers on foot through cities across the world. Street photography is a genre with a low success rate but an immense investment of time and effort. This book distills that journey into a carefully curated selection, capturing the essence of my work on the streets.

Artistic vision and approach: Your work captures the “decisive moments” of everyday life in bustling cities. How do you train your eye to spot these moments, and what draws you to a particular scene or subject?

I go out with an open mind, without narrowing my focus to specific aspects of daily life. Fixating on particular elements risks excluding the unexpected—the very moments that might hold the image I’m looking for. Instead, I trust that what’s worth capturing will reveal itself naturally. The joy lies in being fully present, absorbing everything, and allowing the scene to unfold. My only job is to be ready when the moment appears in front of my lens. That openness—being receptive to anything that tells a story—is essential to my work.

None of the images I have ever taken—and thus none of the images in this book—are ones I could have envisioned or deliberately sought out beforehand. Reality holds far more surprises than my imagination ever could. That’s why I let things come to me, guided only by intuition. Just as we cannot control the moments we capture, they—like in almost all creative art forms—often reflect something of ourselves. By trusting our instincts, we inevitably draw from the "backpack" of our own life experiences.

I tend to look beyond the surface, perhaps as a result of my own life story. In the context of my street photography, I am not naturally drawn to the light or humorous sides of daily life. Instead, I seek out what lies beneath—the layers that often go unnoticed. This inclination often leads me to images that explore the less obvious, sometimes more uncomfortable aspects of life. But I relate to these moments, and I believe they are important to show.

Have you ever had an instinct about a scene, taken the shot, and only later realized its deeper meaning?

This happens to me all the time. In fact, my best photos all share this quality—an element that makes them special, yet one I didn’t notice while shooting. More often than not, it’s these unexpected details that define a picture for me.

Storytelling in photography: Each of your photographs invites viewers to imagine their own stories. How do you ensure your images are open-ended enough to spark this level of engagement?

I believe this directly relates to how I select and approach a potential scene. I don’t hide, I don’t shoot from the hip—I am fully present and integrated into the environment. This allows me to invest more time in a single shot, to frame it deliberately, and to wait for the right moment. More often than not, it’s anticipation that leads to the image—imagining what might happen next and how the elements within the frame could come together to tell a story. I look for entry points or indicators of a strong image. Once you, as the photographer, recognize the story within the elements presenting themselves, the image takes form even before you press the shutter. It emerges in the process, somewhere between discovery and documentation.

I call this the photographic reflex—a complex chain of thoughts that, over time and with experience, transforms into instinct. I compare it to the process of jazz musicians or boxers. Neither consciously thinks through complex movements in the moment; they have mastered their craft to the point where execution becomes second nature. For me, photography works the same way—it all happens in the space between discovering and pressing the shutter. The act of pressing the button is the easiest part of it all.

I approach every place with an open mind—not unprepared, but always without prejudice. For me, it is essential never to shy away from encounters as a consequence of my photography. I am rarely invisible, but I am usually well-integrated. Integration and transparency matter more to me than striving for invisibility.

Being invisible often means hiding—and that is something I never do. Instead, I become part of the space, part of the scene. Psychological and non-verbal cues play a crucial role in this process. These signals help people develop an unspoken trust or, at the very least, ensure that they do not perceive me as a disruption in their environment.

On the street, photography is about seeing, being ready, and discovering the unexpected. A strong instinct for the street and its people is invaluable. One should never shy away from an encounter—fear is never a good companion. That’s why I approach almost everyone with openness. People can sense whether your intentions are honest and transparent or not.

This silent, unspoken trust is the key to becoming just another presence in the scene—the classic fly on the wall. It allows me to capture authentic moments without artificial interference or distancing myself from the context.

Challenges and perseverance: Walking for hours and months in metropolises must come with unique challenges. What obstacles did you face, and how did you stay motivated and inspired throughout the project?

Gratitude—for the ability to dedicate time to my photography and experience life in so many different places.

Ambition—to find the next image that speaks and contributes to the body of work.

Beyond the images, it is the human connections that fascinate me most—the immersion into other lives, cultures, and realities. One encounters all facets of human existence: tragedy, joy, loss, triumph, ignorance, and humanity—to name just a few. The emotions of everyday life are endlessly diverse and ever-present in countless forms.

It is a privilege to be both an observer and a documentarian, to wander urban landscapes for months at a time, capturing fleeting moments. But it’s not just the photographs that remain; I take home friendships and places that have become familiar. These experiences enrich me in ways that go far beyond photography.

In almost every city I visit, I have friends and acquaintances. There’s always a sofa or a guest bed waiting somewhere. And then there are the moments that happen while photographing—the chai in the middle of the night on Istanbul’s Galata Bridge with a Kurdish refugee, an honest conversation in a back alley of New York with people who own nothing but what they carry, or exchanges with those standing at the front lines in Ukraine, just to name a few. These are people whose lives exist far beyond the boundaries of an average comfort zone. These encounters stay with me—they are just as valuable as the photographs themselves.

The challenges are just as varied. Shooting on the street for months at a time can be physically and mentally exhausting. Self-doubt is always present, and failure is an inevitable part of the process—one that isn’t always easy to deal with. Continuity is not always joyful; more often than not, it’s about persistence—showing up and doing the work rather than waiting for inspiration to strike.

As Chuck Close once said: “Inspiration is for amateurs—the rest of us just show up and get to work.”

Was there ever a time when frustration made you question the process? How did you push through?

A healthy level of obsession is essential for any creative project. The drive must be strong enough to endure both physical and mental challenges. Frustration is inevitable—a constant but manageable presence. Early on, I accepted that most images won’t work and that failure is part of success. Every day, I move between triumph and struggle—and I’m at peace with it.

My real frustration isn’t with photography itself but with visibility, social media, and self-promotion. On the streets, I can manage failure and self-doubt—through physical exhaustion, shifting my perspective, or simply embracing the privilege of observing. On slow days, a good conversation or a quiet café can reset me.

The digital world, however, is different. Unlike photography, where effort leads to tangible results, the online landscape is ruled by algorithms and ad revenue. I accept this, but it remains the hardest part of sharing my work.

Role of the photographer: As a street photographer documenting the lives of overlooked individuals, how do you navigate the ethical considerations of capturing and sharing these intimate moments?

As a photographer, my responsibility is neither to manipulate nor distort reality. At its core, photography should serve people, not work against them. Ethics and morality play a central role in street photography, especially since we often engage with strangers without prior consent. That’s why we must always act with respect—particularly in situations that feel inappropriate or when it becomes clear that our presence is unwelcome.

When people approach us as street photographers, we owe them an explanation of our actions. Transparency is essential. I don’t hide behind my camera; my subjects should have the opportunity to express themselves or object to being photographed. Secretive or “blind” shooting from the hip contradicts this approach.

Equally important is a reflective attitude when selecting images. We must consciously decide which photographs to publish and which to withhold. This decision-making process requires balancing public interest with the dignity of the individuals depicted. These ethical considerations shape the entire workflow—from capturing to editing to presenting an image.

I see it as my responsibility not to misrepresent people or alter reality. Every image must be chosen and presented in a way that upholds these principles. As street photographers, we should always be able to justify our decisions while remaining true to our ethical standards.

Ultimately, as street photographers, we are dedicated to documenting the human condition—embracing reality as it is. Beyond the ethical considerations mentioned, I do not believe we have the right or authority to filter reality. If certain aspects of life appear repeatedly, in large numbers, or with overwhelming presence, who are we to censor them based on personal preference? Our role is to observe and document—not to shape reality to fit our own narratives.

Connection with the environment: Cities like New York, Paris, and Amsterdam have distinct rhythms. How do you adapt to the character of each city to ensure your photographs resonate with its essence?

I spend long periods in each city I photograph. I spend several months a year in New York, a pattern I repeat in Istanbul, Paris, and other cities. The more time you invest, the more you begin to understand the subtle, non-obvious inner workings of a place.

Wherever I go, I follow the same routine: waking early, walking for as long as possible, and returning to base only when exhaustion sets in. This typically means covering 10 to 15 kilometers on foot each day—sometimes for months at a time. With time and distance, clarity emerges. I begin to understand a city’s social dynamics, its people, its light, and its character.

My approach is systematic: I start from a defined location and gradually expand outward. I walk every street in widening circles, at different times of the day, until I identify key locations and preferred routes. Once established, I refine these routes, fine-tuning them to maximize the potential for images.

To truly go deep, I immerse myself completely—staying in the flow for weeks, eliminating distractions, and focusing entirely on the assignment. Few things bring me greater joy than the privilege of engaging with a place, its culture, and its people on this level. At times, the process becomes almost meditative—fully immersed, yet observing from a distance, connecting the broader context with the smallest details and fleeting moments.

Have you ever had an interaction with a stranger that changed how you saw a place or influenced your photography?

Everywhere I go, I arrive as a stranger. I can learn the streets, navigate the city, but the soul and character always come from the people. Whether it’s fellow street photographers I meet, the coffee shop I return to daily, or brief conversations with strangers in passing, these moments shape my understanding of a place. The better you know a place, the more your perspective shifts.

Technical and creative tips: Your use of black-and-white photography emphasizes emotion and spontaneity. What advice would you give photographers on using monochrome to highlight the essence of a scene?

I appreciate visual concepts, and from the very beginning of my street photography journey, I knew I wanted to follow certain traditions inherent to the genre. My goal has always been to create a body of work that is visually cohesive and maintains a strong conceptual identity.

On one hand, the historical context naturally led me to black-and-white photography. On the other, I see its strength in its ability to distill an image down to its essence: the moment, the content, the composition, and the light. The clarity of black-and-white images is a major advantage in street photography, as color can sometimes distract from the essence of a moment or reduce an image to its color palette alone, rather than allowing for deeper layers of meaning.

That said, I deeply admire many street photographers who masterfully use color within the genre. But for me personally, the graphic quality of an image feels stronger when color is absent.

I believe the quality of an image is defined by the tension between two perspectives: Henri Cartier-Bresson's belief that a photograph must first be visually and geometrically compelling to draw the viewer in, and Robert Capa’s Magnificent Eleven—his D-Day series, which, despite its technical imperfections, remains unmatched in relevance.

To create a compelling black-and-white image, beyond the subject and content, light and composition are key. In street photography, this means finding the light, integrating architectural or geometric elements to highlight the subject. These are constants—elements that must be present for an image to work. The search itself becomes essential; we must seek out the conditions that make a great image possible. We cannot create them—neither in post-production nor in reality. We have to find them.

And in the end, the story always wins. Technical perfection is secondary to narrative. As Cartier-Bresson famously said: “Sharpness is a bourgeois concept.”

Street photography as a dialogue: Stella Kramer described your work as beginning a conversation rather than ending it. How do you use composition, light, and movement to create this sense of dialogue in your images?

The technical aspects of photography define an image’s readability. That’s why I strive to capture the best possible picture, even though I have no control over the elements within the frame at the moment of capture. Being open and fully present in that moment is essential to me. If I am distracted by anything self-centered, I might overlook key details—small elements that could be integrated or used to enhance the unfolding story. Often, it’s a matter of millimeters—a slight movement, an unnoticed object in the background, or the precise alignment of the frame with a graphic element—that can elevate an image from a simple capture to a compelling story.

But ultimately, the story is key. I want to ignite the viewer’s imagination, to evoke an emotion—any emotion. Which feeling it sparks is entirely beyond my control. However, in my view, if an image fails to create that spark, it doesn’t truly work.

For me, a successful image touches, communicates, and feels personal. It reaches the viewer on an emotional level. Yet how an image resonates and what emotions it evokes are beyond the photographer’s direct influence. We are merely the senders, while the viewers—the receivers—interpret the message in their own way.

Without emotion, without a point of connection, an image loses its impact or fails to resonate at all. The closer an image comes to the viewer in both content and form, the stronger its subjective effect. For me, this sense of closeness is what makes an image truly special.

Context also plays a crucial role. Images that reveal connections, hold historical relevance, or document moments in time are particularly meaningful to me. They fulfill one of photography’s core functions—preserving stories, emotions, realities, and the essence of an era.

Advice for aspiring photographers: For those starting in street photography, what are the most important skills or mindsets they should cultivate to capture authentic and impactful images?

Street photography doesn’t require much in terms of technical expertise or equipment. But if you want to take it further, it demands a high level of personal engagement and a deep familiarity with your gear. The beauty of it is that you have full control over how intensely you want to practice it. To begin, all you really need is time, a camera, a single lens, and a good pair of shoes.

When deciding what to photograph, make it personal. Follow your own principles, your own instincts. Let your pictures speak about something that truly matters to you, rather than shooting aimlessly without direction. We all have aspects of life that resonate with us—things we find important, worth preserving, or worth questioning. Identify those. Follow them.

When you know why you want to tell a story, motivation is no longer something you chase; it becomes the force that drives you forward. As Elliott Erwitt once said: “Photography is an art of observation. It has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.”

The best work comes from within. Make it personal.

To discover more about this intriguing body of work and how you can acquire your own copy, you can find and purchase the book here. (Kehrer Verlag, Amazon)

More photography books?

We'd love to read your comments below, sharing your thoughts and insights on the artist's work. Looking forward to welcoming you back for our next [book spotlight]. See you then!