Finding Something Sacred in the Ordinary: How Lisa Barlow’s Holy Land U.S.A. Teaches You to See Through a Camera

Welcome to this edition of [book spotlight]. Today, we uncover the layers of 'Holy Land U.S.A.,' by Lisa Barlow (published by STANLEY/BARKER). We'd love to read your comments below about these insights and ideas behind the artist's work.

There is a difference between taking a picture and truly capturing a feeling.

A photograph isn’t just about pointing a camera at something—it’s about seeing, understanding, and being part of the moment. Anyone can press a shutter, but not everyone can make an image that feels alive. The difference is in how a photographer connects with what’s in front of them, whether it’s a place, a person, or a fleeting interaction.

This is what Lisa Barlow discovered when she found Holy Land U.S.A.

Lisa Barlow didn’t go there looking for a project. She was a young photographer with a camera, exploring the world around her. But standing in that strange little park, surrounded by crumbling statues and the hum of the town below, something clicked. It wasn’t just about what was being photographed—it was about why. That realization changed the way she saw, and it shaped every picture she took after that.

There is a difference between taking a picture and truly seeing.

The Book

In Holy Land U.S.A., photographer Lisa Barlow revisits her early work documenting an unusual roadside religious theme park in Waterbury, Connecticut. What began as a curious stop in 1980 drawn by the towering cross above the city—evolved into a deeply personal exploration of place, faith, and community.

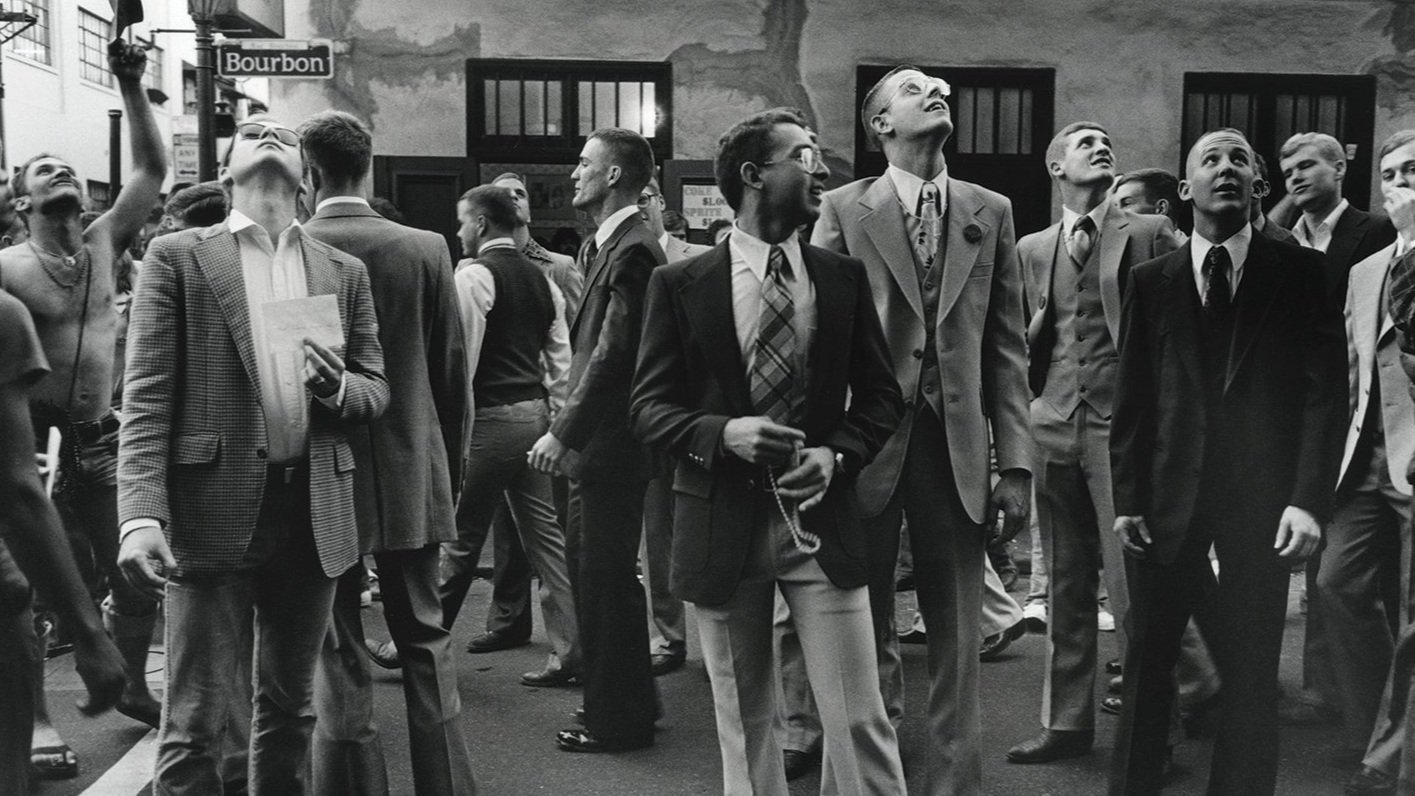

Set against the backdrop of a declining industrial town, Barlow’s images move beyond the kitsch of miniature biblical scenes to capture the people who made Holy Land their own: families posing by the crucifix, a carpenter shaping a statue of Christ, and the vibrant life unfolding in the streets below. Through her lens, she finds not just a fading monument, but a profound connection to the everyday resilience and quiet holiness of the people she meets.

Archived for decades before publication, this body of work reflects a formative period in Barlow’s journey as a photographer. Her images embody the traditions of American documentary photography where observation turns into storytelling, and a single frame can hold both humor and humanity. (STANLEY/BARKER, Amazon)

Discovery of Holy Land U.S.A.: In the summer of 1980, you encountered the replica of Jerusalem known as Holy Land U.S.A. in Waterbury, Connecticut. Can you describe your initial reaction upon discovering this site and what compelled you to document it?

I had just learned to drive and was proud of the freedom it represented. I could rent a car! Never mind that all I could afford was an old beater from a company called Rent-A-Wreck, it was all mine for the weekend. That first rental was an oversized 20-year-old Buick with a motorized front seat which was stuck in the most forward position. I drove up Route 69 with my knees scrunched against the steering wheel, windows open to the September air and the fuming exhaust pipe, getting out to stretch my legs at yard sales and farm stands. At one point, it was impossible not to notice the humongous cross looming over the highway, glinting in the sun. It seemed like good place to stop.

I hadn’t heard of Holy Land U.S.A. yet. In a bizarre revelation I only learned this year, my mother had gone with her city planning class to study the 18-acre site in 1963, the year I turned five. Recently built by a man named John Greco as a tribute to the life of Jesus, I think she was looking at its layout and the impact this place had on the surrounding streets of Waterbury, then nicknamed The Brass Capitol of the World, famous for the watches, buttons and bullets it manufactured.

For me, though, all I could think about when I entered the little religious theme park, was “Thank God I have my camera!”

The whole place was delightfully peculiar, an array of little white foot-high structures representing Bethlehem and parables from the Bible; hand-built out of plaster, rebar, cement, cyclone fencing and lots of paint. There was the Inn with a No Vacancy sign, a rickety Stairway to Heaven, a weedy overgrown Garden of Eden.

To be honest, it was all sort of funny in a charming way. And the juxtaposition of this little miniature world with the smokestacks and houses below was exciting to photograph. I once joked this was the place I found religion. Not a formal one, but that exhilarating feeling a person gets when the world suddenly makes sense. For me, at that moment, looking through the viewfinder of my camera, I understood that you could have an idea about something and convey that idea to someone else. I could tell a story or a joke or describe a feeling or a fact using my eyes, my brain and my camera.

Was there a particular image from that first visit that really cemented this realization for you?

This is the one of the first photographs I made in Waterbury. I hadn’t yet seen Holy Land, but I was interested in the cross on the hill and stopped my car to make the picture. I could see that the graveyard somehow linked to the cross, and the cross seemed to be blessing the place. That sidewalk was leading somewhere, which turns out to be my future. I had the idea of the play Our Town in my head, and I could see that this was a place where generations of people had lived. There is construction going on, so however peaceful, things are changing.

Later in the darkroom, I understood how the image worked formally, how important that cloud is in the upper left corner, how important the many lines leading one’s eye throughout the frame.

Here’s one that didn’t make it into the book. I love this picture! I think I made it on my second visit to Holy Land. You see the back of a plywood façade of a castle-like structure. Beyond, you see the city of Waterbury spread below. And there in the middle, a carload of people who look like they might be getting ready to picnic. There is so much to see and think about here—a false-fronted idea of a place juxtaposed against a real place; a family with their car which must have driven on the roads below, its trunk and doors open, making it as important a character as the people it just disgorged. I understood the power of cars, how the American landscape had been shaped by them, and how important they were to family life and our idea of ourselves as people in charge of our destinies.

Integration into the Waterbury Community: While photographing Holy Land U.S.A., you became deeply involved with the local community. How did your interactions with the residents of Waterbury influence the direction and depth of your project?

I went back a few times to photograph Holy Land, but it wasn’t long before that first sense of wonder grew to encompass not just the place, but the people who were there to experience it. Clearly, Holy Land meant a great deal to this community. Whole families flocked there to take pictures of themselves with Jesus on the Cross. I shared coffee in the shade of a plywood camel with a carpenter who was carving a figure of Christ out of an enormous log. I met the nuns who lived in the little convent by the front gate.

Then I became curious about Waterbury below. I remember being hungry for lunch and driving down the hill and parking close to the Town Green. You can see in my contact sheets how I navigated the city in those first forays. I ate arepas at a counter in a tiny storefront, a Big Mac at McDonalds where children were having a birthday party. I went into Woolworth’s to buy penny candy and marvel at beach towels of the Last Supper. And at some point, I began to talk with children playing in the streets and in their back yards.

If my first pictures were about me describing a physical place, soon there were actors in the frame, all of them in action. I was hardly much older than the teenagers I was photographing. Maybe this made it easier for them to invite me indoors, and easier for me to accept their invitations. The kids clearly wanted me to take their picture, but at some point, it was as if the camera wasn’t there. I no longer felt like an outsider. We were just hanging out.

It was maybe at this point that I began to think of my time in Waterbury as a project and not just as a location where I was taking pictures to take back to photo class. It’s important to note that I was still in school during the week. Photography was my favorite subject, and I was learning from some of the great photographers of our time. Larry Fink and Tod Papageorge were my teachers. We were studying The Americans by Robert Frank. Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander gave guest lectures. My Major was American Studies, and I was learning about great American cities in literature and history classes. It seemed like Kismet to use the work I was showing in Photography for my Senior Project.

It would take four more decades for me to see that the Holy Land U.S.A. I thought I was photographing encompassed a much wider term of the word “holy,” that it was the people who lived there, rather than the place they lived in, who manifested holiness, and that to be holy could simply mean how one lived one’s life within the quotidian constraints of a normal day.

Was there a specific moment when you realized the community itself had become the heart of your work?

Here is another picture that did not make it into the book. I took it early on during one of my first forays into town. I had met a wonderful woman in Holy Land, a nun named Sister Marian, who became a friend. She had invited me to a church celebration at St. Cecilia’s one Sunday where a child was being baptized. The family invited me home to celebrate. I hadn’t yet been inside many of the homes where I later felt comfortable, but I immediately loved the chaotic energy of the place and the warmth of the people. This was a different kind of excitement than what I felt when I was more inside my head making visual sense of a landscape.

Here is an image from later in the series, where I am fully embedded in the community, no longer an invited outsider, but someone who is so taken for granted that I could document these intimate encounters using a flash and not call attention to myself.

Balancing Kitsch and Earnestness: Holy Land U.S.A. has been described as both kitschy and earnest. How did you navigate these contrasting elements in your photography to convey the site’s unique character?

I think there is always a bit of earnestness in what is kitschy. Certainly, the people who built Holy Land U.S.A. did so in full earnestness. So, it’s in the eye of the beholder to perceive either quality, or both. It would have been so easy to have stayed in the more one-sided comical realm. I adore things that are odd and funny. But I was also beginning to feel a kind of love and I felt like I owed it to the people who were becoming my friends to show their depth.

Technical Approach and Equipment: You utilized a Leica M6 with a 35mm lens for this project. How did this choice of equipment influence your shooting style and the intimacy of your images?

I had just bought my Leica M6 with money I earned at a summer job. This was the camera my mentors and heroes were using. I was astonished by Henri Cartier Bresson’s photographs and had been incredible lucky enough one day to happen upon him as he worked. It was outside the old ICP on the Upper East Side, and he was lurking on the corner of 94th Street watching something across Fifth Avenue by Central Park. He was diminutive in a tan raincoat and at first you couldn’t see his camera. It was covered in black tape, attached to his hand by a black strap, but suddenly there it was at his eye and then furtively by his side again. I was too shy to say hello. But I did go home and black out the label on my camera.

In terms of size, the Leica is the perfect 35 mm shape to hold in one hand. I love the proportions of the rectangle. Without knowing in a formal or art historical sense why it was pleasing, it just seemed like the perfect shape to tell a story. I loved the theater as a teenager and had enjoyed acting in plays. In a way, you can think about the rectangle of the viewfinder as a kind of proscenium. The drama on stage is contained within it.

Revisiting Archived Work: The photographs from this project remained archived for decades before being published. What was it like to revisit these images after so many years, and how did your perspective on them evolve over time?

During the Pandemic I learned how to scan my negatives. What a strange time that was anyway, but it became stranger for me as I began to be immersed in the past while feeling trapped in the present.

I was seeing my life as I had lived it 40 years earlier and I began to make soundtracks of the music of the time. My diary entries and notes from 1980 and 1981 weren’t extensive, but they rooted me in that alternative reality. What might have been a hazy memory of my youth suddenly pulled into focus. I am incredibly grateful for this in a number of ways, and forgive me if this sounds corny, but it allowed me to love my young self in an almost parental way. “You are going to be alright,” I want to tell her.

In terms of the pictures, I knew they were good then. I had taken them to a publisher after graduation, but the response wasn’t what I wanted. People were looking at them and seeing poverty or threats instead of humanity. I’m glad I waited. My dad had the best reaction when he saw the work for the first time this year. After carefully turning every page, he said, “any of these people could be me.” He didn’t mean literally, but he saw himself in the exuberant kids playing on the street, in the little boy sitting with his balloon, and in the dad dancing at a wedding.

When you revisited them, did anything about the work surprise you or feel different from how you originally saw it?

Remarkably, I remembered key images clearly. I think what surprised me is how lucky I had been to gain the trust of so many different people.

I was filled with a sense of deep gratitude in seeing the work again. And, a profound sense of loss. Many of the people I photographed are no longer alive. One of the families, who is not portrayed in the book, died in a fire in 1982.

There is also a deep sense of nostalgia for a different time, one before cell phones and personal computers and digital cameras. I’d like to think that I can make work like this today, but honestly, it feels much harder in this age of surveillance to feel as easily trusted with my camera as I was in 1980.

Portraying Resilience in a Declining Town: Waterbury was experiencing economic decline during your documentation. How did you approach capturing the resilience and spirit of its residents amidst these challenges?

It was the ‘80’s. NYC was in financial distress. New Haven was a mess. Waterbury was just one of many blighted New England cities in steep decline. Factories that had employed a robust workforce were shuttered or barely staffed. The people in some of the homes I visited lived close to the poverty line. Those were easy details to see. But once I had begun to make friends there, other qualities took precedence. If you are laughing with people, sharing meals with them, celebrating weddings and birthdays with them, those are the things that matter most.

Influence of American Studies Background: With a background in American Studies, how did your academic insights inform your photographic exploration of Holy Land U.S.A. and its cultural significance

One of my American Studies classes was Sociology. I was encouraged to take field notes while I was creating my project. I can tell that my teacher was excellent from the extensive notes he made to my submissions. But I should confess this here - I don’t think I was as good a student in his class as I could have been. You can tell that I was far less interested in taking objective notes than in participating in people’s lives.

My favorite class in American Studies was Richard Brodhead’s English class where we read Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie and analyzed Thomas Eakins paintings in the Yale Art gallery. It was here, thinking about human drama and the visual ways to describe a way of life, that I’m sure influenced me the most as I learned to tell my own American stories.

When I published Holy Land U.S.A., I could have described the different ethnicities of the workforce, or the year Cass Gilbert designed the City Hall, but I chose to leave all that out in this publication. What matters more to me is what you bring to the work with your own experiences and references.

Emotional Connection to Subjects: Your images convey a deep empathy and connection with your subjects. How did you build trust and rapport with the individuals you photographed, and how did this relationship impact the authenticity of your work?

I made this work at a tricky personal time. By 1980, I had returned to college from a year away. My parents were divorcing, and my grandmother had just died not long after witnessing an infamous murder in NYC. Yale allowed me to take a year off between Sophomore and Junior year and I took a boat to France where I enrolled in theater school and took a job as a “fashion spy” photographing store windows at night and sending the slides to American companies who copied Paris’s trendsetting looks.

Back at school, I was out of step with my classmates and a little lonely. While I still had plenty of friends on campus, I wasn’t sure how I fit in. But in Waterbury I felt like I was a part of people’s families. One family, in particular, was influential. They were generous in including me in family events, inviting me to spend the night if it was too late to drive home. On Mother’s Day they hosted a pig roast, they created big birthday celebrations for their children. Mammoth pots of food were always bubbling on the stove, moonshine was brewing in the basement, chihuahuas and kittens scooted in and out of the house, music was playing, people were dancing. While this wasn’t my family, they were kind enough to allow me to feel a part of it, and I’m sure they could feel my gratitude. Looking at the pictures for the first time after so many years, I laughed when I realized that I have emulated much of the happiness I found in that house, down to the booze in the basement, the lively kitchen table and the puppies and the cats.

If my vulnerability helped create trust in some situations, in others it might have been a shared sense of joy. With Kenny, the boy with the boom box, for instance, we had so much fun together. And this helped Kenny show me his vulnerability. That word “connection” is a two-way street. We each had to share something.

Advice for Emerging Documentary Photographers: Reflecting on your experience with Holy Land U.S.A., what guidance would you offer to photographers embarking on long-term documentary projects, especially those focusing on unique cultural sites and communities.

I’m going to give this advice to myself right now too, because feeling at home somewhere in a way that allows you to share what is “authentic” and special about it, requires a pretty radical honesty. Even when I am on the F Train in Brooklyn photographing in 2025, and I am being subtle with my camera, I am trying to share something of myself when I am taking a picture. Call it a kind of love. If you don’t feel empathy for what you are photographing, even a train car or a landscape, it’s hard for the viewer to feel it either.

With a project like Holy Land, U.S.A., where you are welcomed into a community, that sense of empathy must be even stronger. You have to see yourself in the people you photograph for the work to read as true.

Go ahead and be specific. Tell the story of a place in all its uniqueness. But keep it universal too. You want someone to say “I know that feeling. That could be me.”

To discover more about this intriguing body of work and how you can acquire your own copy, you can find and purchase the book here. (STANLEY/BARKER, Amazon)

More photography books?

We'd love to read your comments below, sharing your thoughts and insights on the artist's work. Looking forward to welcoming you back for our next [book spotlight]. See you then!